Vocabulary

- Decimal system – 십진법

- Knuckles – 손가락 관절

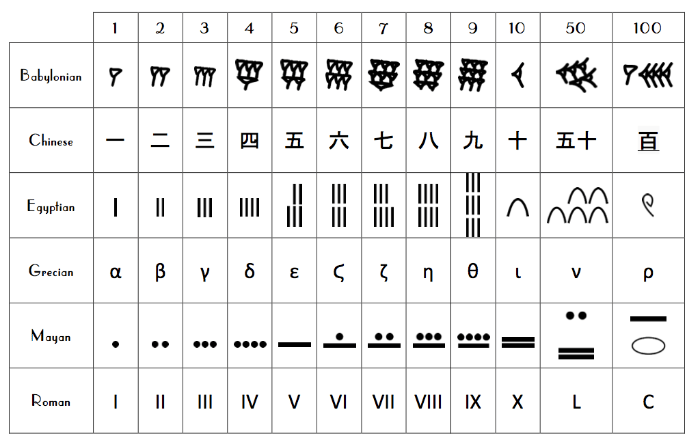

- Ancient – 고대의

- Calculate – 계산하다

- Receipt – 영수증

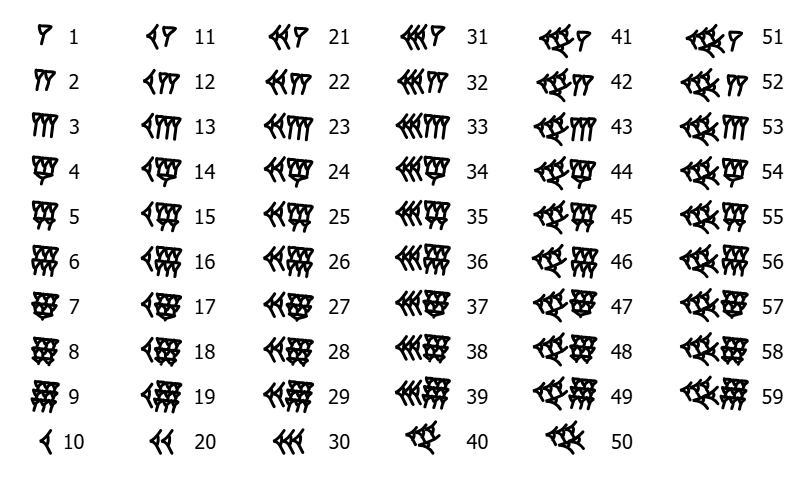

- Base 60 – 육십진법

- Tax collector – 세금 징수인

- Algorithm – 알고리즘

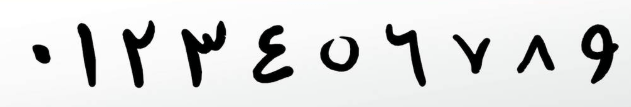

- Digit – 숫자 (0-9)

- Trade – 거래

- Record keeping – 기록 관리

- Mathematician – 수학자

- Place value – 자리값

- Numeral – 숫자 기호

- Abacus – 주판

- Tally – 눈금 계산

- Base system – 기수 체계

- Clay tokens – 점토 토큰

- Segment (finger) – 손가락 마디

- Symbol – 기호

- Placeholder – 자리 표시자

- Subtract – 빼다

- Divide – 나누다

- Addition – 덧셈

- Multiplication – 곱셈

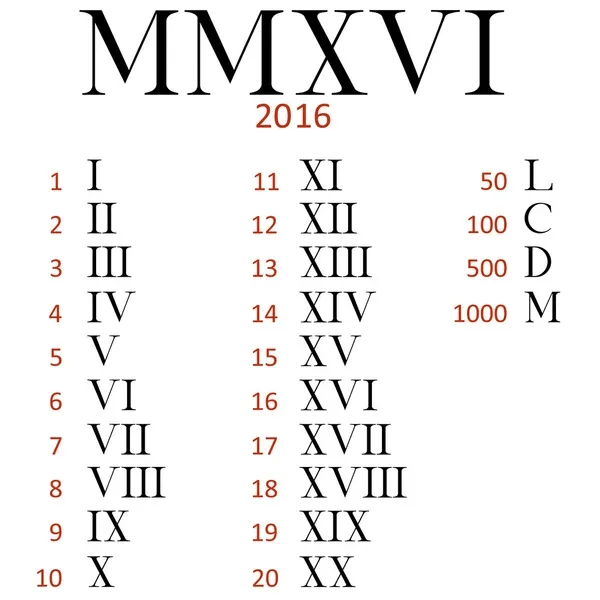

- Roman numerals – 로마 숫자

- Position – 위치

1] Imagine grocery counters but only sticks, no numbers. How would you keep track of 7 apples?

2] If people only used Roman numerals, how would they write 40 plus 9?

3] Suppose you had no symbol for zero—how would you write a hundred and five?

4] Could you add 27 and 35 if your numbers reset at 9 (no tens)?

5] Why didn’t ancient people need a symbol for thousands when they lived in small villages?

6] If your counting system let you reuse symbols based on position, what happens when one place is empty?

7] Imagine trading sheep using just I, II, III… up to X. How hard would it be to record 57 sheep?

8] Think of counting with fingers only. How would you record 23 without losing track?

9] If zero also meant “nothing,” why might early societies avoid calling it a number?

10] How would banking or trade be harder without a placeholder like zero?

11] When no digits beyond five existed, how would people handle 12 or 18?

12] Why wasn’t “big math” (like algebra) needed when early counting was for daily life?

13] If people lived in places with calendars and time measures based on 60, how would their math look?

14] Suppose you invented zero in your culture—how might philosophy or writing influence that idea?

15] If someone invented a numeral for “void,” how would you convince others it’s useful?

16] Without a positional system, how many different symbols must we learn to write 10, 100, 1000…?

17] What everyday task becomes simpler if you can write 603 instead of 63?

18] Could early calculators like abacuses replace zero? Why or why not?

19] If you traveled from India to Europe in 600 CE, how might merchants explain zero?

20] Why would Europe resist adopting a new system with only ten symbols instead of dozens?

Did You Know?

- The Babylonians (around 400 BCE) used a base‑60 system and even had a placeholder for empty places—though zero wasn’t a number yet.

- The Maya civilization independently developed a symbol for zero in their base‑20 calendar—surprising, right?

- In India during the Gupta period (~500 CE), Aryabhata used zero as a placeholder, while Brahmagupta later defined subtraction like 5 – 5 = 05 – 5 = 05 – 5 = 0, and treated zero as a full number

- Weirdly violent: in Cambodia there’s a stone slab from AD 683 listing temple offerings, including a zero dot in “605”—the oldest known decimal zero, hidden away during civil war then rediscovered in 2013

Myth Busting: Many think Romans had zero—but they didn’t use a symbol for it. Their numerals didn’t need a placeholder because they wrote numbers additively, not positionally.

Fingers, Stones, and Sheep

Long before calculators, or even pencils, humans had a much simpler tool for math: fingers. And if you ran out of fingers? Well, there were always toes, pebbles, bones, or notches in sticks. Early humans didn’t need to do complex algebra. They just needed to count sheep, keep track of how many mammoths didn’t run away, or remember how many angry neighbors they’d borrowed arrows from. For that, your hand was the original math device. Ten fingers? Ten things. Done.

In some places, counting was a bit more advanced. The Sumerians in Mesopotamia, around 3000 BCE, developed clay tokens to represent numbers for trade. A cone meant one sheep, a disk might mean ten goats, and if you were unlucky enough to forget what the symbols meant, you’d invent the world’s first accounting problem. These clay records became the first receipts. So basically, early math started because someone didn’t want to get cheated on their goat deal.

But things got wild in Africa: the Ishango bone, a 20,000-year-old tally stick, may have been used to count in base 12. That’s right—some ancient people may have skipped ten and gone straight to twelve. Why? Possibly because they counted knuckles. That’s right. Look at your hand. Each finger has three segments. Count with your thumb and you can get to twelve. And that, my friend, is either genius or very bored prehistoric math.

Yet all this cleverness had a problem. None of it used place value. You couldn’t write “21” as “two tens and one.” You had to use a new mark or more symbols. Want to count to a thousand? Better sharpen that stone—you’ll be writing all day.

1] Why did early people use bones, stones, and fingers to count?

2] How might the Ishango bone’s base 12 system work with hand segments?

3] Why is it difficult to work with numbers if there’s no place value system?

4] A tally stick has 12 marks. Each mark means 5 chickens. How many chickens is that?

5] A base 12 system uses 12 as the ‘next place.’ If you had 3 full twelves and 2 leftover, how much is that?

How Romans Made Math Harder

Roman numerals look cool on clocks and movie titles—but using them to actually do math is like trying to eat soup with a fork. Romans wrote numbers with letters: I = 1, V = 5, X = 10, L = 50, C = 100, etc. So the number 49 was written as XLIX. Try subtracting that from LXXXVIII without crying.

These numerals had no place value. In our system, 21 and 12 are different because of the position of each digit. In Roman numerals, each number had its own unique mash-up of letters. There was no shortcut. You couldn’t just carry the 1, line up columns, or do long division unless you were also a gladiator in mental gymnastics. Even multiplication was best done with pebbles or counting boards.

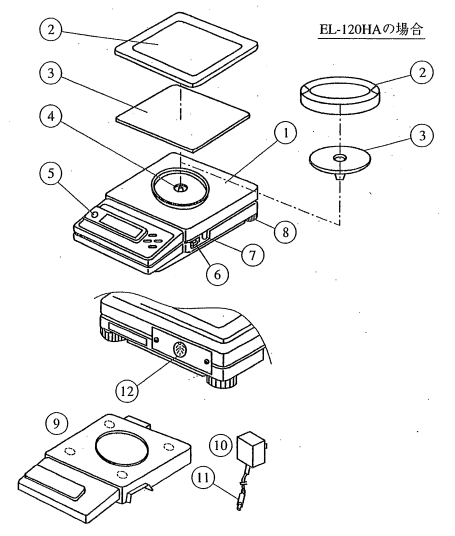

The system was mainly used for record keeping—like how many soldiers were paid, or how many amphorae of wine were delivered. When Romans needed to do big math, they often used an abacus. It’s like having a laptop where the keyboard is smarter than the software.

What’s funny is that Roman numerals stayed in Europe for over 1000 years, even when everyone knew they were terrible for calculation. Why? Because they looked official and ancient—just like using Latin to impress your friends at dinner.

1] Why is it difficult to do multiplication using Roman numerals?

2] How did the lack of place value make Roman math harder?

3] Why do Roman numerals still appear today, even though they’re not used for real math?

4] If XLIX + IX = ?, write the total in both Roman and modern numbers.

5] A Roman soldier delivers L amphorae of wine. If he drops XX on the road, how many are left?

Zero: A Very Late Arrival

Zero is the most powerful nothing in history. And strangely, it took thousands of years for anyone to invent it. For most of history, people had no need to write “nothing.” If you had no goats, well, you had no goats. You didn’t need a number to remind you. In fact, to many early cultures, the idea of nothing as a number seemed ridiculous—like selling someone a bag of air and calling it a cow.

But by around 500 CE, Indian mathematicians realized they needed a way to write “nothing” in a position. If you wanted to write “203,” how could you show the zero without a symbol? Without it, people might think you had “23”—which could be a huge problem if you were counting taxes, or soldiers, or cows with a grudge.

Brahmagupta, a 7th-century Indian genius, was the first to treat zero like a proper number. He even gave it rules: any number minus itself is zero, and zero divided by anything is still zero (though dividing by zero? Still not allowed). His ideas traveled slowly through the Arab world, where scholars like Al-Khwarizmi (yes, the word “algorithm” comes from him) spread them to Europe.

Before that, people faked zeros by leaving blank spaces or using dots. But a dot doesn’t have the same power as a real zero. Once zero got in, the whole number system became smoother, smarter—and finally able to do real math.

1] Why did people resist using zero for so long?

2] How did Brahmagupta’s rules help make zero a real number?

3] Why is it important to have a symbol for zero in large numbers?

4] If a merchant writes “507” but forgets the zero, what wrong number might people read?

5] A farmer had 30 cows. He sold 30. Using zero, how many are left?

How the Decimal System Changed Everything

At last, along came a number system that was simple, elegant, and—best of all—made math less awful. It had just ten digits (0–9) and used place value. Instead of inventing a new symbol for every number, this system reused the same digits in different positions. Suddenly, you didn’t need fifty different marks to write 88. You just needed two.

This place-value system with a zero was first used in India, and by around 800 CE, it was spreading through the Arab world into Europe. Europeans called it “Arabic numerals” because they learned it from Arab mathematicians—though the Arabs called it the Indian system, since that’s where it came from. Basically, everyone agreed it was brilliant, but no one wanted to give credit where it was due.

With this system, addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division became far easier. Merchants could keep proper records. Architects could calculate building sizes. Farmers could track crops. And taxes? Oh yes, the tax collectors loved it.

But Europe was suspicious. They thought the new numbers looked like magic. Some even believed that using Hindu-Arabic numbers was wicked or un-Christian. So for a few centuries, people used Roman numerals in public, and the decimal system secretly at home—like sneaking candy into bed after brushing your teeth.

1] Why was the decimal system easier than Roman numerals?

2] How did place value help people do math faster?

3] Why were some Europeans suspicious of the new number system?

4] If “203” means two hundreds, no tens, and three ones, how would “230” be different?

5] A builder uses digits 2, 3, and 0 to show lengths. What is the difference between 230 and 320?

Homework

Writing Tasks (Choose any 10 to do on one page each)

- Describe how early humans used body parts to count and why it worked.

- Explain why Roman numerals were difficult to use for shopping.

- Imagine life without zero—how would you write large numbers?

- Choose a culture (like Maya, Babylonian, or Indian) and explain their number system in your own words.

- What makes the decimal system easier than earlier number systems?

- Write about the first time zero was treated like a number. Why was it important?

- Tell a short story of a Roman merchant trying to do math and struggling.

- Explain how place value helps you understand numbers better.

- Pretend you’re a teacher in ancient India introducing zero to your students—what would you say?

- If you could invent your own number system, what would it look like and how would it work?

Debate Tasks (Choose a side and explain your argument)

1. Should we still teach Roman numerals in school?

- Side A: Yes, because it shows how numbers developed and helps us understand history.

- Side B: No, because they are outdated and not useful in real life.

2. Is zero the most important invention in math?

- Side A: Yes, because it made modern math and technology possible.

- Side B: No, because we could still count and trade without it.

3. Should children learn other number systems like base 12 or base 60?

- Side A: Yes, because it helps them understand how math can work differently.

- Side B: No, because the decimal system is enough and easier to use.

Summary of Key Points

Numbers didn’t begin with fancy symbols—they started with fingers, bones, and stones. Early people needed to count, not to solve equations, but to survive. As trade and farming grew, so did the need for recording numbers more clearly, leading to tally marks and early systems like base 60.

The Romans created a system that looked important but worked terribly for math. Without place value or zero, simple calculations were difficult, and real work needed tools like the abacus. Despite being smart warriors, they made lousy math tools.

Zero, shockingly late to the party, changed everything. Invented and developed in ancient India, it allowed people to write big numbers clearly and do proper math. But not everyone accepted it at first.

The decimal system finally brought order to chaos: only ten symbols, reused in different positions, could build every number we use today. It took time, travel, and a bit of rebellion to spread, but once it did, math was never the same.

Final Questions for Review and Test

Answer the following questions in full sentences. If you don’t know the right answer, do try write something, but add a (?) mark, and later we can look at it together.

1] What simple tools did early people use to count things?

2] Why was counting with tally marks useful but limited?

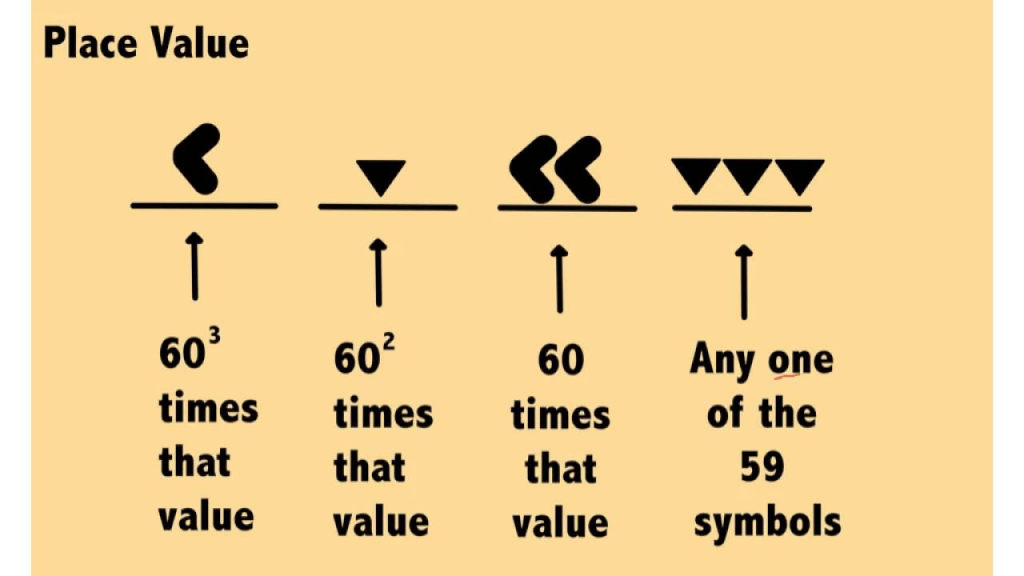

3] What number system used base 60, and what kind of symbols did it use?

4] What was the main problem with Roman numerals for doing math?

5] How did the lack of a zero make place value difficult to use?

6] Who was Brahmagupta, and what did he do with zero?

7] Why do we call our numbers “Hindu-Arabic numerals”?

8] What does “place value” mean when writing numbers like 203 or 507?

9] Why didn’t early societies need numbers for thousands?

10] What are some examples of early counting systems before the decimal system?

11] Why do Roman numerals still appear on buildings and clocks today?

12] What made the decimal system simpler than earlier systems?

13] How is an abacus different from modern calculators?

14] What would be difficult to calculate using Roman numerals?

15] Why did some Europeans resist the use of zero and the decimal system?

16] What was the first known symbol used for zero?

17] What makes zero special as a number?

18] What do you think is the easiest way to count without modern numbers?

19] How did Indian and Arab mathematicians spread new math ideas?

20] What does it mean when we say the decimal system uses only 10 digits?