1] If you sell fruit at a stall, how do you keep track of who owes you money, the prices, and how many apples you sell each month?

2] What happens if you agree to trade 3 goats for 6 chickens, but someone changes the deal later?

3] If you’re buying silk from a city far away, how would you track how much you paid and how much you made?

4] How can you remember how much money 10 people owe you, all at different interest rates?

5] What happens if someone accidentally adds money twice in your records?

6] How do you prove someone paid you if you forgot to write it down?

7] Why would it be hard to do business using only Roman numerals?

8] What tools might help people in large cities count better than fingers or stones?

9] If your country uses gold coins but your neighbor uses silver bars, how do you trade fairly?

10] Why would a banker need to use multiplication and division daily?

11] What if your ship full of spices sinks—how does math help deal with the loss?

12] Why is it useful to write down every single trade in the same way?

13] What problems might arise if two different people use different ways of adding interest?

14] Why would a merchant want to know the exact value of 1/3 of something?

15] If you don’t understand math, could someone trick you in a deal?

16] What happens if your writing system doesn’t have decimals?

17] Imagine you lend someone 100 coins. They return 105 after one year. How much interest is that?

18] Why would factories and machines need very accurate math?

19] What kinds of math would you need if you’re planning a shipping route for trade?

20] Why would inventors and engineers need more math as they built bigger machines?

Did You Know?

- The word “bank” comes from the Italian word banca, meaning bench—because early bankers did business sitting on benches in the marketplace.

- In the 1400s, Florence had over 80 different coins in circulation. Currency conversion was a full-time job.

- Luca Pacioli, the father of accounting, was also friends with Leonardo da Vinci—and may have helped with the math for some of Leonardo’s inventions.

- Some early banks collapsed completely because a single clerk made a mistake in a ledger—and people lost all their savings.

Myth Busting:

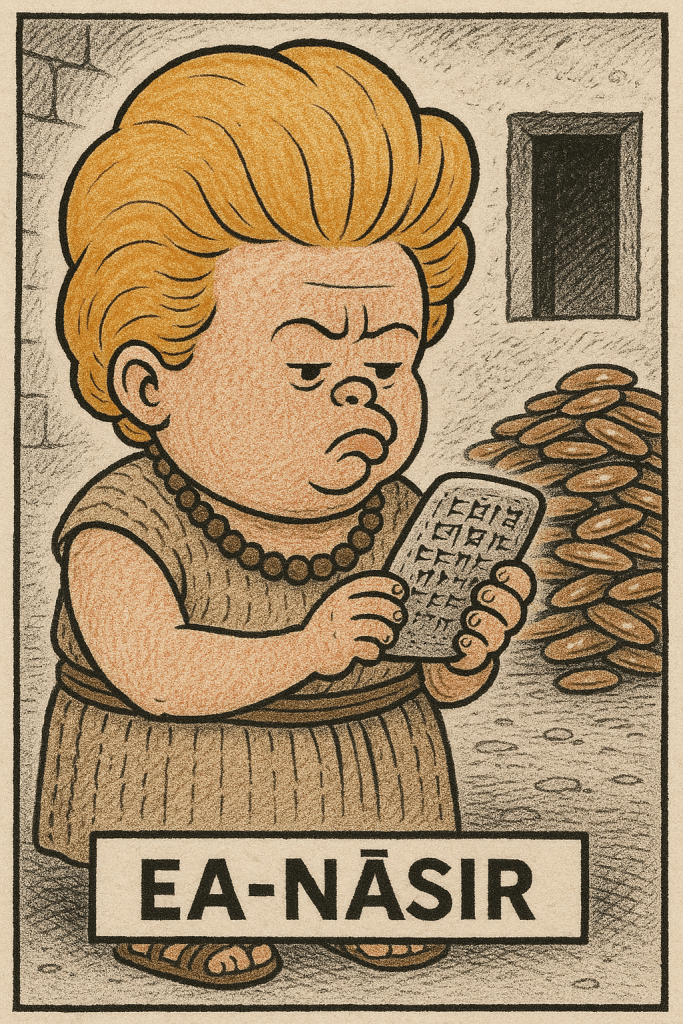

Many people think ancient traders just used “barter” (swapping goods), but from at least 2000 BCE, complex trade records, loans, and interest calculations already existed in Mesopotamia—some written on clay tablets that still survive today.

Vocabulary

- Trade – 무역

- Market stall – 시장 좌판

- Merchant – 상인

- Interest – 이자

- Currency – 화폐

- Ledger – 장부

- Double-entry – 복식부기

- Bank – 은행

- Arithmetic – 산수

- Fraction – 분수

- Decimal – 소수

- Algebra – 대수학

- Accountant – 회계사

- Profit – 이익

- Loss – 손실

- Credit – 외상

- Debit – 차변

- Invoice – 계산서

- Exchange rate – 환율

- Coinage – 동전 화폐

- Numerals – 숫자

- Recording system – 기록 체계

- Capital – 자본

- Investment – 투자

- Engineer – 기술자

- Workshop – 작업장

- Weights and measures – 중량과 측정

- Silk Road – 비단길

- Trade route – 교역로

- Industrial – 산업의

From Market Stalls to Merchant Empires

In the beginning, trade was a humble affair: one fish for one loaf of bread, no questions asked. But things got complicated fast. When traders started crossing borders, languages changed, money looked different, and suddenly one fish might cost 17 bronze coins in one town and 23 in another. You could no longer rely on memory and a firm handshake. You needed math.

By the 1200s, cities like Florence, Venice, and Bruges were buzzing with trade. Markets grew, and with them came new problems: “How much silk can I buy with 40 florins?” “How do I split 13 barrels of oil between 7 merchants?” These weren’t math puzzles. They were daily survival. That’s when the need for big math was born—not in dusty libraries, but on busy docks where ships loaded with spices and wine came in from distant lands.

Traders began writing things down. Not just what they bought and sold, but who owed what, when, and how much interest was agreed. The notebook became mightier than the sword—at least in business. Merchants who couldn’t do quick math risked losing fortunes. If you sold 500 rolls of wool and forgot who paid in advance, you were in deep sheep.

As trade networks expanded—thanks to the Silk Road, camel caravans, and salty sea dogs—so did the math. Deals grew bigger, and prices fluctuated. The math of the market was becoming as powerful as the goods themselves.

1] Why did trade become more complicated over time?

2] How did math help merchants deal with changing prices and currencies?

3] What would happen if a trader didn’t keep records of who owed money?

4] A merchant has 500 rolls of silk and sells them in packs of 25. How many packs can he sell?

5] If 1 wool roll costs 4 coins and he sells 500, how many coins does he earn?

Money, Interest, and Math Tricks

Let’s talk about interest. Not the kind you feel in a new video game—but the kind banks use to grow money. Around the 13th century, merchants figured out that if they lent someone 100 coins and asked for 110 back a year later, they could make a tidy little profit. Simple enough, right? But when you’re lending to five people in five cities using five types of coin… well, suddenly, you need more than fingers to do the math.

This is when Fibonacci entered the picture like a mathematical superhero. In 1202, he wrote Liber Abaci, a book that explained how to use the Hindu-Arabic numeral system (our numbers today) to solve real trade problems. It wasn’t about theory—it was full of practical problems: “How much will you earn if someone pays 4% interest over 3 years?” or “If 60 florins become 72 florins, what’s the rate?”

Thanks to interest, people could borrow and invest. But they could also lose money. If you made a mistake in the decimal point—oops!—suddenly your profit disappeared. Traders learned to love fractions and percentages, not for fun, but because one misstep could ruin a voyage.

Even currency exchange demanded tricks: 1 ducat might equal 7 groschen or 3 florins in a different city. That meant learning to multiply, divide, and sometimes guess like a wizard in a cloak made of gold receipts.

1] What does it mean when someone earns interest on money they lend?

2] Why was Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci important for merchants?

3] Why could decimal mistakes cause serious problems in trade?

4] A banker loans 200 coins at 5% yearly interest. How much is owed after one year?

5] A trader exchanges 3 ducats per florin. If he has 15 ducats, how many florins can he get?

Accountants and Algebras

Imagine you’re running a bakery in Florence in the year 1400. You sell 30 loaves to one customer and 50 to another. You owe your flour supplier 80 coins. You borrowed 100 coins from your cousin, but paid back 30 already. Your head is spinning. You need a system.

That’s where double-entry bookkeeping arrived to save your crusty bread. This method, perfected in Italian trading cities, recorded every coin coming in (credit) and every coin going out (debit)—always balanced, like a scale. If the numbers didn’t match, something was fishy (or someone was). You could instantly see where money was being made—or lost.

Luca Pacioli, a sharp-eyed monk with a love for ledgers, published the first textbook on this in 1494. He didn’t invent it, but he made it famous. His guidebook taught merchants how to avoid disaster with simple rules: don’t spend money you haven’t recorded, always match your credit and debit, and write it all down. In pen. Clearly.

Behind this system sat a deeper idea: algebra. That mysterious tool where letters represent numbers helped people create formulas for tracking profits, losses, and interest. Medieval bankers weren’t just good with coins. They were using early math logic, centuries before spreadsheets.

1] What is double-entry bookkeeping and why is it useful?

2] How did Pacioli help people manage their money better?

3] Why might a bakery in 1400 need algebra?

4] A baker sells 50 loaves at 2 coins each, but spends 80. How much income is that?

5] He owes 80 coins for flour and earns 100. What’s his profit?

Steam Power and Decimal Dreams

By the 1700s, math had taken over. Banks weren’t just small wooden stalls anymore. They had buildings, vaults, ledgers the size of small children, and accountants who wore wigs so large they probably stored extra quills inside them. But even this was just the warm-up.

Trade wasn’t just local now—it was global. Ships crossed oceans. Companies formed with thousands of investors. Prices of goods like cotton, tea, and sugar rose and fell like roller coasters. Math had to grow up fast. Decimal systems became standard. Interest rates, insurance premiums, exchange rates—all required precise math.

Then came the machines.

The Industrial Revolution was knocking at the door with steam engines, metal gears, and factories the size of castles. Suddenly, math wasn’t just for trade and money. It was for engineering. If your numbers were wrong, your bridge collapsed. If your calculations were sloppy, your machine exploded (and possibly took your mustache with it).

At this point, math had moved far beyond merchants. It was helping inventors, engineers, and factory owners design the modern world. But how? What kind of math powered the new age of machines?

Well… that’s a story for the next lesson.

1] Why did trade and banking become more complex by the 1700s?

2] What new fields needed math during the rise of industry?

3] How did decimals and accurate calculation help engineers?

4] If a machine needs 7 gears per engine and a factory builds 120 engines, how many gears are needed?

5] If a company makes 15% profit on each engine and sells 200, how many engine profits are earned?

Homework

Writing Tasks (Choose any 10 to write about on one page each)

- Who was Nanni, and why was he upset? (Link)

- Describe how trade became more difficult as markets expanded.

- Explain how interest works and why traders used it.

- Write about a fictional merchant who makes a big mistake with decimal math.

- Explain why double-entry bookkeeping is still used today.

- Describe the importance of Liber Abaci and what it taught.

- Imagine you’re a banker in Florence in 1450—describe your daily work.

- Explain how algebra helped merchants do business more carefully.

- Tell the story of a merchant who didn’t record his sales—and what went wrong.

- Explain why decimals became important in the world of banking and trade.

- Imagine you’re an engineer in 1750 building a steam engine. What kind of math might you need?

Debate Tasks

1. Should math be taught differently for students who want to run a business?

- Side A: Yes, because real-world business math is different from classroom problems.

- Side B: No, because basic math is useful in all areas.

2. Is it fair for banks to charge interest?

- Side A: Yes, because it’s how they earn money and take risks.

- Side B: No, because it makes people pay more than they borrowed.

3. Should we still learn about old accounting systems like double-entry?

- Side A: Yes, because they teach logic and organization.

- Side B: No, because computers do the work now.

Summary of Key Points

As trade grew from simple market stalls to giant merchant empires, math had to grow too. Early traders needed more than counting—they needed systems to track sales, debts, and interest. From this need, people developed ledgers, bookkeeping, and even used algebra in real life.

Interest wasn’t just a fancy math term. It was a way to grow money—and to lose it if you weren’t careful. Books like Liber Abaci helped explain these ideas using the new decimal system. Traders who used it had an advantage over those still using clunky Roman numerals.

The invention of double-entry bookkeeping made money management more precise. It helped detect errors and keep businesses honest. It also introduced logic and algebra into daily financial life, centuries before anyone used spreadsheets or calculators.

Finally, the Industrial Revolution began to demand math on a whole new scale—one that reached beyond banks and into workshops and factories. Machines were coming, and they needed math to run. That’s where we’re heading next.

Final Test Questions

Answer the following questions in full sentences. If you don’t know the right answer, write something and add a (?) so we can review it together.

1] Why did traders start using ledgers during long-distance trade?

2] What kinds of math problems came with currency exchange between cities?

3] What is interest, and how does it help banks make money?

4] What made Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci so useful for merchants?

5] What’s the difference between Roman numerals and Hindu-Arabic numerals in business use?

6] How did fractions help traders split goods fairly?

7] What’s one danger of making a mistake with decimal points in banking?

8] How does double-entry bookkeeping help prevent financial mistakes?

9] Why did accountants need algebra in medieval times?

10] Who was Luca Pacioli and what was his contribution to business math?

11] Why did decimal systems become more important in global trade?

12] What’s the purpose of writing down both credits and debits in accounting?

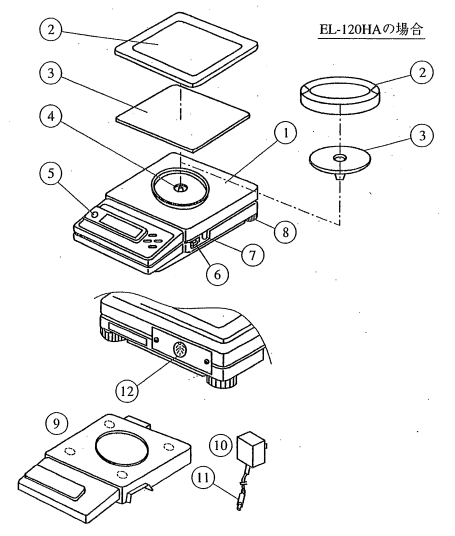

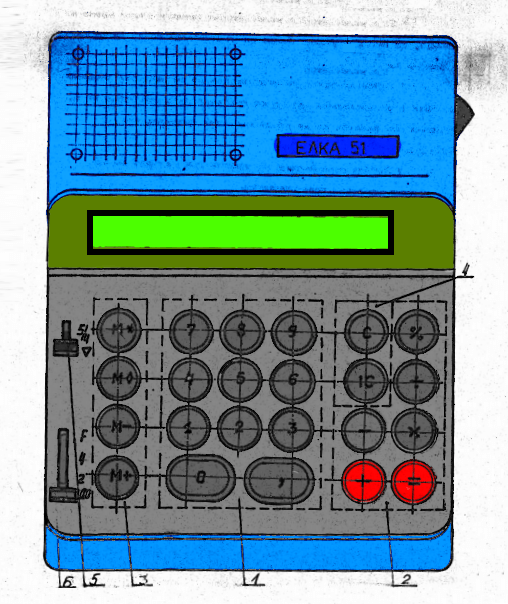

13] What tools did merchants use before calculators?

14] How did trade influence the growth of mathematics?

15] How did engineers use math during the start of the Industrial Revolution?

16] What are some risks of doing business without good math records?

17] How could currency confusion lead to unfair trades?

18] What role did ledgers play in early banking systems?

19] Why were precise measurements important in factories?

20] How did math change from being only about trade to being needed in machines?